Still relatively unknown, Rwandan coffee is the country’s number one export, and one Japanese man intends to share it with the world

As he crushes the berries, Kawashima shows that the ripeness of the berries can be determined by their juices.

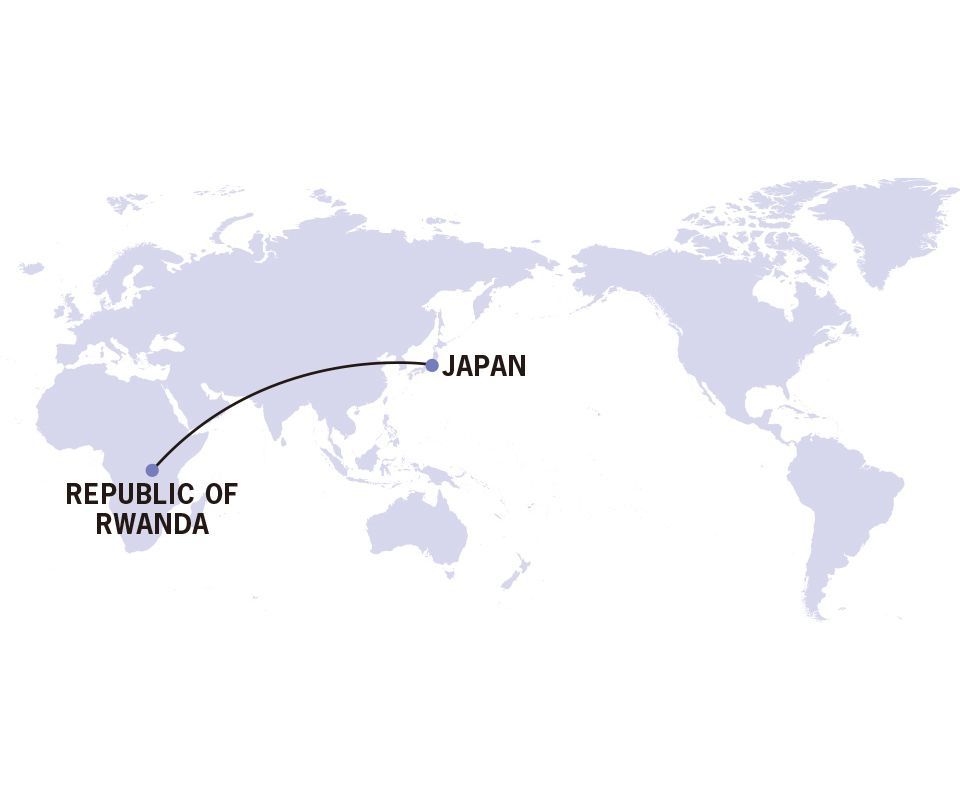

Rwanda boasts a coffee industry that spans over a century. Its high elevation, temperate tropical highland climate, and fertile volcanic soils provide an ideal environment for the plant to thrive, and government backing has improved production quality. However, growers had been unable to boost the economy and improve wages, so the government called on Japan for assistance.

The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) surveyed growers to ascertain awareness of quality standards for each stage of production: selection, processing, distribution and sales. The two countries bolstered their ties in 2017 with a partnership deal between JICA and Rwanda’s National Agricultural Export Development Board (NAEB) to improve crop yields, coffee quality, and marketability.

Spearheading the deal is Yoshiaki “José” Kawashima—known as the Coffee Hunter because of his knowledge and expertise combined with an ability to discover rare varieties and talented producers around the world. Governments and royal foundations regularly call on him to work alongside farmers and provide counsel on techniques to improve production.

Rwandan coffee producers listen to Kawashima as he explains how to make terraced fields.

One of the secrets to delicious coffee is the “selection” process of the coffee berries. Kawashima instructs Rwandan producers not to mix mature berries with those that haven’t ripened.

Consider Kawashima the bridge between coffee-consuming countries and coffee-producing countries. His personal mission is to “change the world through coffee,” spearheading sustainable coffee production. And, he says it all starts with researching the history of the region.

“Rwandan coffee comes from a variety introduced to the area by German missionaries in 1903, which had adapted well to the land around the small village of Mibirizi in southwest Rwanda,” Kawashima says. He continues, “This cultivar ultimately took the name Bourbon Mibirizi. However, disease had seemingly wiped it out.”

While visiting Mibirizi, a forlorn coffee plot behind a church caught Kawashima’s eye. Upon inspection, he realized it was a Bourbon Mibirizi, so he harvested its ripe berries, roasted them, and prepared a cup of the forgotten brew. It struck him that he had discovered Rwanda’s hidden treasure. This coffee’s richness and complexity were unlike any other coffee he had tasted.

Kawashima had found a new mission: to bring this coffee back to life and build a global brand from this national treasure. When asked how he interacted with the locals, Kawashima smiles and replies, “Initially, the local farming community didn’t offer much support. Japan’s not a coffee producer, so, for them, it didn’t make much sense to listen to me.”

From his experience with agrarian societies, he knew that to gain their trust he would have to sweat and toil alongside them. Over time, he forged a bond with the community, and their skepticism toward him turned into a belief in his cause. The time had come to bring these seedlings back from the brink of extinction. With the locals on his side, Kawashima could switch his focus from the seeds to the fields.

Deforestation along the hillsides combined with heavy rains had eroded the land, wreaking havoc on the plantations. To curtail this, the locals and Kawashima used terraced fields and planted shade trees as well as underbrush to prevent soil runoff. To rejuvenate less productive trees, they employed a “cutback” technique to offset unchecked growth.

“The farmers knew the trees would die if over-trimmed, which was a little disturbing for them, but a few months later, the trees looked noticeably better, and they saw that I was right. That lifted everyone’s spirits,” recalls Kawashima.

Two years into the project, Kawashima believes the Mibirizi beans will be ready for market in about five years, thanks to steady improvements in cultivation. After cultivation, the next step is bean selection, followed by processing, sales, and exporting. All are connected and important steps within the industry.

“I’m nurturing these new skills in the locals. This way they can instruct new generations,” says Kawashima.

Soon, Rwandan coffee will be one of the most coveted coffees in the world—elevating the country and its people—thanks to passionate young farmers who learned from the Japanese Coffee Hunter.

Yoshiaki “José” Kawashima

As the son of a wholesale coffee roaster, Yoshiaki “José” Kawashima, known as the Coffee Hunter, has spent his entire life around coffee. He studied at the Salvadoran Institute for Coffee Research and then worked for a major coffee company, developing plantations in Jamaica, Indonesia, and Hawaii. Then, in 2008, he founded Mi Cafeto, achieving his dream of creating a sustainable business importing and selling coffee in Japan.