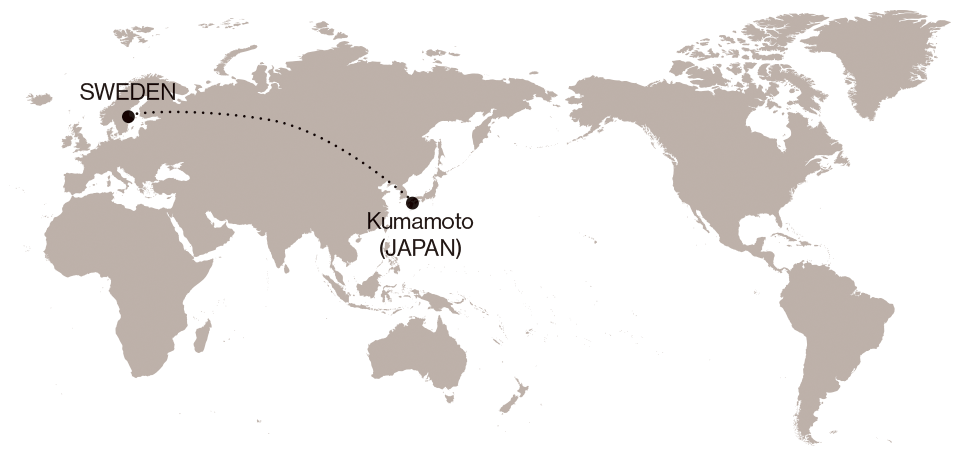

Hans Koga, a Swedish craftsman of koshirae (outer sword components) in Kumamoto, is not only helping preserve traditional techniques but also conveying the soul of the samurai to the world and future generations.

The Japanese sword, which was once a samurai weapon, now attracts many overseas enthusiasts as a piece of art. In addition to being appreciated for its functionality on the battlefield, it is also revered for its aesthetic value. The two major factors that determine this beauty are the cylindrical saya (sheath), which houses the blade, and the tsuka (hilt). Those components of the sword are collectively called koshirae, and one of the few craftsmen still actively producing koshirae is a Swede by the name of Hans Koga.

“When I was a boy, I had the opportunity to watch a demonstration of iaido (martial arts using Japanese swords) in Stockholm, and I was completely fascinated by the Japanese swords. With their extraordinary power, they really seemed to possess the soul of the samurai,” he recalls.

After graduating from a polytechnic high school, he worked as a ship carpenter. But when a major injury forced him to quit that line of work, his interest in Japanese swords was reignited. He moved to Japan and while studying at a sword studio, he learned about the various regional styles of koshirae. Among them he became particularly attracted to the Higo-koshirae of Kumamoto Prefecture in Kyushu, southwestern Japan (Higo is the old name for Kumamoto).

Japanese swords vary in style depending on the region. The Higo-koshirae is a style that marries function with beauty. It was established by a local lord who was also a master in sado (Tea Ceremony).

“The Higo-koshirae have robust and functional structures with no tolerance for the unnecessary. But, at the same time, they have an aesthetic quality as refined as any tea ceremony. And the proportions of the hilt and the blade are excellent.”

Koga moved to Kumamoto in 2015. While receiving guidance from a retired senior craftsman, he also expanded his skill and knowledge by studying old masterpieces and materials. Even after his house was destroyed in the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake, he says he had no plans to leave the area.

“I want to continue working to pass on this wonderful culture. I also love the people and nature of Kumamoto, and I admire everyone’s tenacity in the face of natural disaster.”

The process called tsukamaki (hilt wrapping) involves wrapping leather cord around the hilt to strengthen it and provide a better grip. The diamond-patterned tsukamaki is so solidly wrapped that it must have been indestructible on the battlefield.

After the earthquake, Koga built a workshop in a corner of a traditional house that is over 300 years old. Benefiting from active promotion using social media, he has a constant backlog of orders from both Japan and overseas. He must work hard to keep up, but he never lowers his standards. “The koshirae, which are made using the same natural materials and traditional techniques as in the olden days, are guaranteed to last for more than one century. They are labor-intensive, but I hope to continue putting all my care into making high-quality pieces as my lifelong work,” Koga says. His words clearly indicate that he shares the strong devotion of the Japanese craftsman who works hard every day at his craft without compromising on workmanship.

HANS KOGA

Born in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1972. After working for a yacht builder in Sweden, he moved to Japan in 2011. He studied at a Japanese sword studio in Tokyo before moving to Kumamoto Prefecture in 2015, where he learned the technique of Higo-koshirae. Today, he works as a koshirae craftsman devoted to both production and restoration.